The Photographs That Captured the Dramatic End to Her Sailing Career

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

August 13, 2020

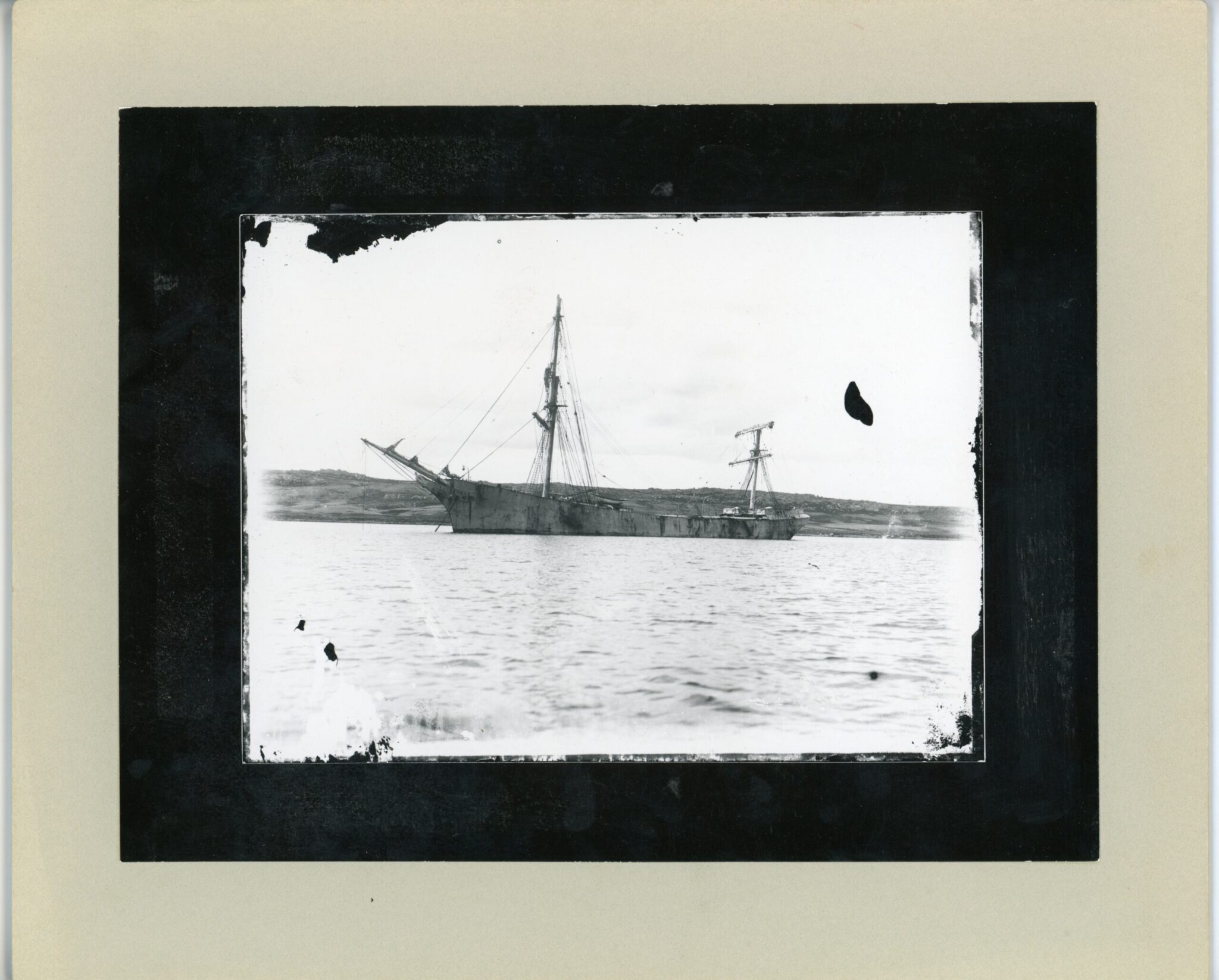

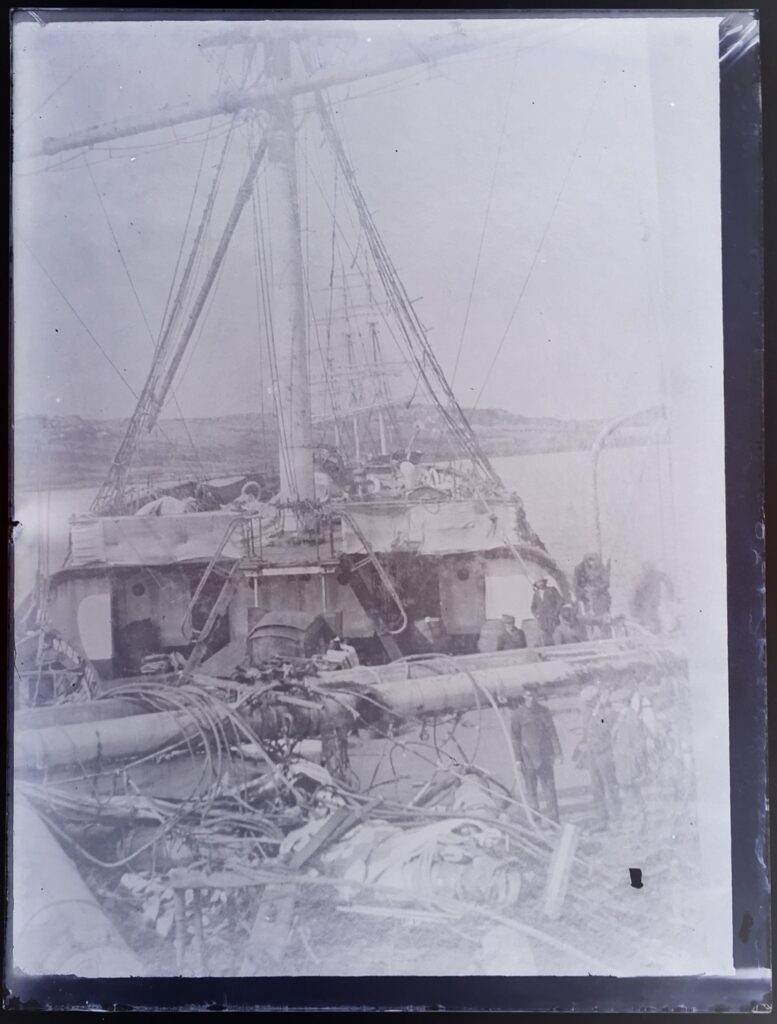

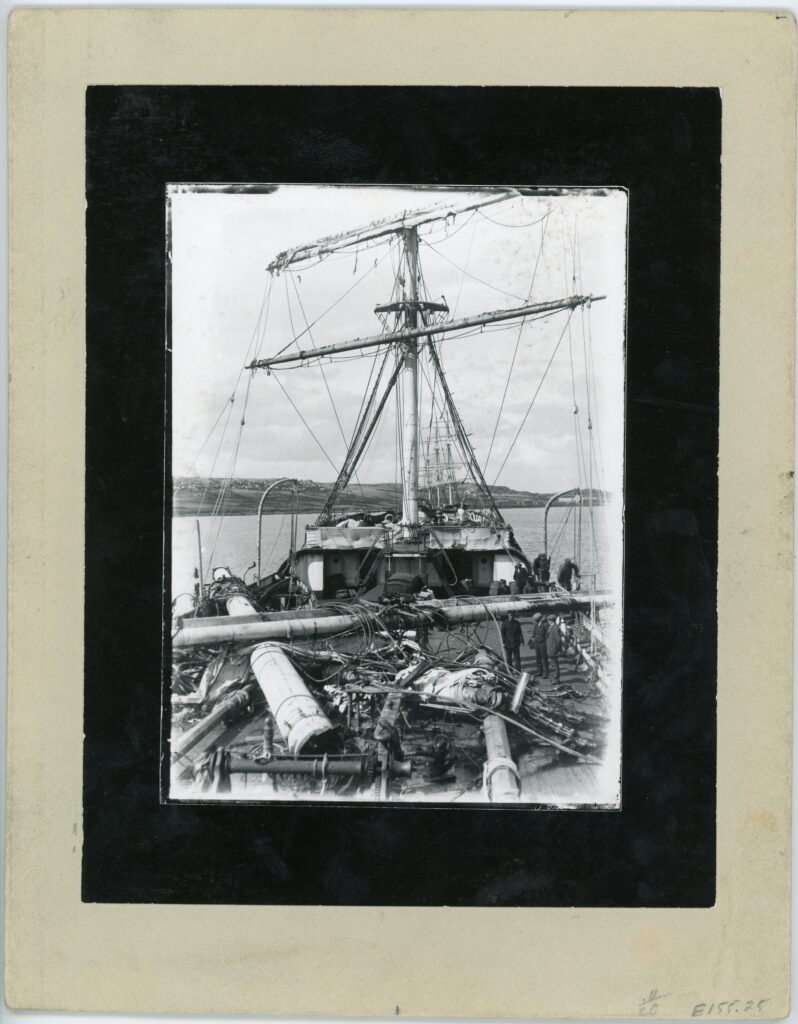

On August 11, 1970, the 1885 iron-hulled Wavertree arrived at the South Street Seaport Museum. This year is our flagship’s 50th anniversary in New York City, in our care, and when I was asked to write a blog post to celebrate her history, I immediately thought of my favorite artifacts that depict her: four photographs that show the damage from her 1910 dismasting off Cape Horn.

Though Wavertree is unique in 2020, as the last remaining iron-hulled three-masted full-rigged cargo ship in the world, she wasn’t particularly special during her sailing career. Wavertree was just one of hundreds of square-rigged sailing ships that sailed the oceans carrying cargo from port to port. Though dramatic events occurred during her 24-year sailing career, including a fire, deaths at sea, and a near miss during “The Great Gale of 1902”, they were considered common occurrences in the risky life of a windjammer. Even Wavertree’s dismasting at Cape Horn was not unusual.

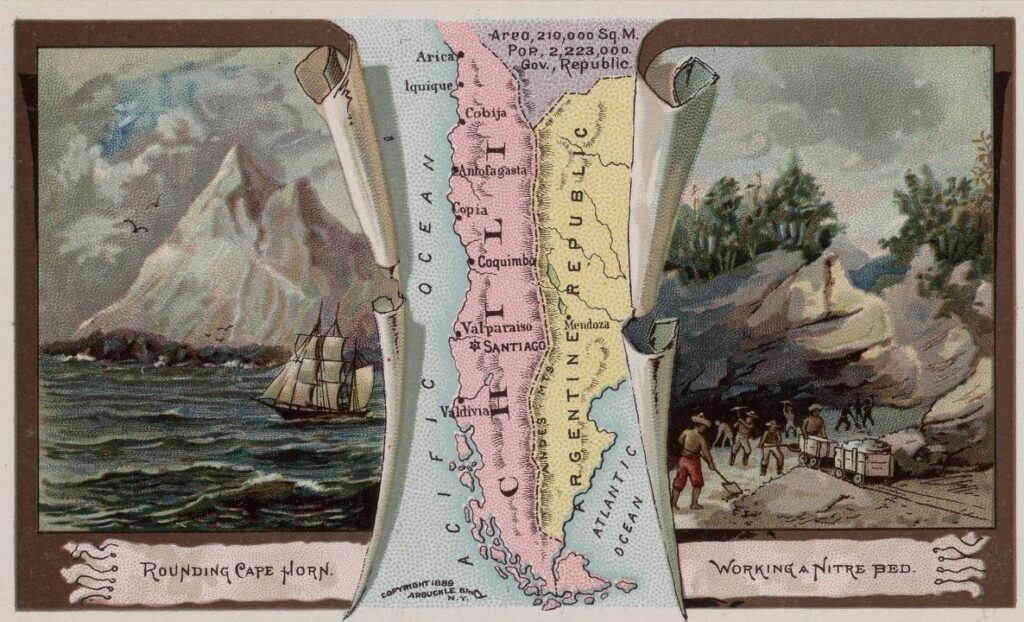

Cape Horn is one of the most perilous sailing routes in the world[1] “Cape Horn: A Mariner’s Nightmare” by Adam Voiland. NASA Earth Observatory posted July 12, 2014.. Before the Panama Canal opened in 1914, the only way to sail between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was to go around the southern tip of South America. The route combines strong winds and currents, as well as frigid waters with risk of icebergs. Hundreds of ships have met their end at Cape Horn.

Wavertree had completed earlier voyages around Cape Horn, but her luck wouldn’t hold through 1910. The ship departed Cardiff, UK, on June 16th of that year with a cargo of coal bound for Talcahuano, Chile. She attempted to round Cape Horn when she arrived in August, and as described in the January 1911 issue of The Falkland Islands Magazine and Church Paper, it did not go well:

“Sailing ships going round Cape Horn usually have rather a thrilling time, but the experiences of the “Wavertree” are of unusual interest. The “Wavertree ”, a large vessel of 2100 tons gross, left Cardiff on June 16th for Talcahuna. When 58 days out she was 200 miles south of Cape Horn, when a violent gale caused her to carry away nearly all her sails. Being practically without canvas, she was unable to proceed on her voyage, but had to run back to Monte Video. There she was refitted and left that port with practically a fresh crew.”

The same article goes on to describe Wavertree’s second attempt around Cape Horn which would be even more disastrous:

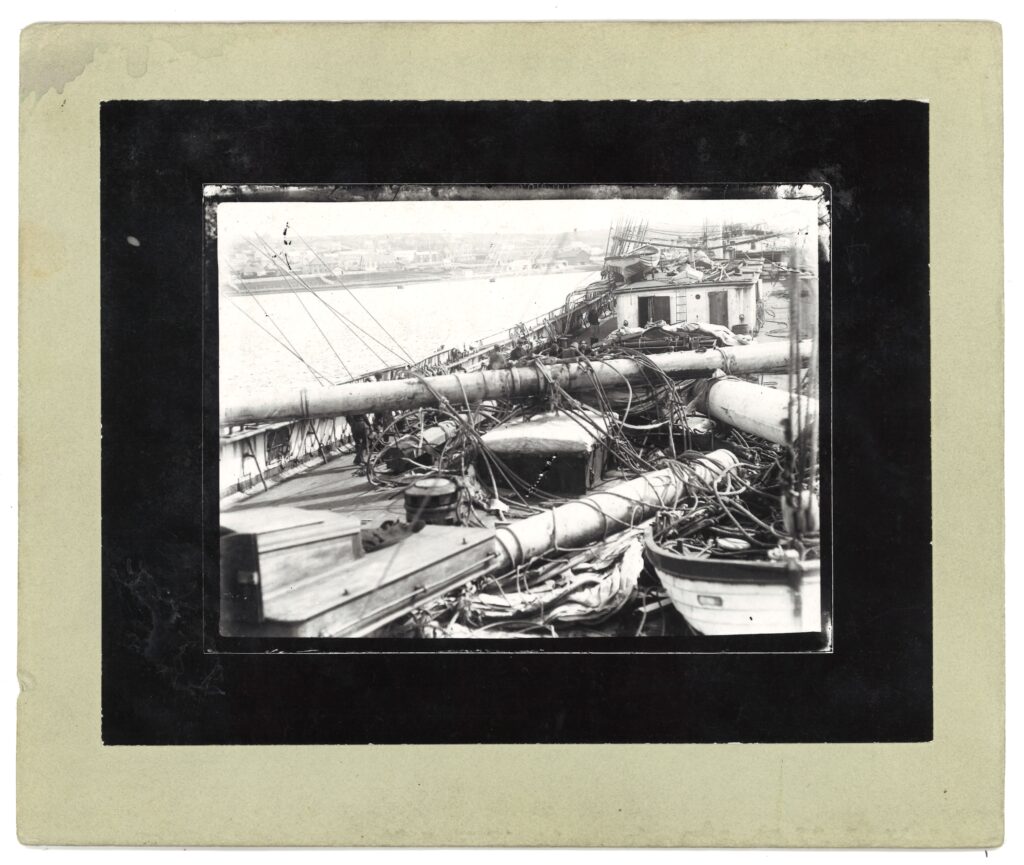

“At the beginning of December the ship unfortunately had very bad weather. The hurricane (‘the real thing’ as one of the crew graphically described it) was so severe that the mainmast snapped in two almost flush with the deck and samshed two life boats and the main pump. The wreckage tore holes in the deck, and through these a great volume of water poured into the lower parts of the ship. And this led to an even more serious calamity.

The water tanks were just under the damaged part of the deck, and through great carelessness on the part of the carpenter these had been less uncovered. The salt water pouring down into the hold filed these tanks so that the water became quite unsuitable for drinking purposes. The carpenter probably was not responsible for his actions as he has since developed mental trouble and is under medical observation in the gaol at Stanley.

Five of the crew were endeavoring to make the deck once more watertight by covering the damaged parts by a sail, when a fresh disaster occurred.

A heavy sea swept the men off their feet and smashed them against the wreckage that was everywhere strewing the deck. So violently were the men hurled by the sea that three of them had their legs broken, one had his leg severely wounded and two ribs of another was fractured. Trouble upon trouble apparently came upon the unfortunate ship: the fore topmast came down from aloft and did further damage to the deck, while shortly afterwards the mizzen topmast was carried away. This ship was now helpless and fortunately for the crew drifted towards the Falklands. She was towed in from near the lighthouse to Stanley on December 2[illegbile]th by the “Samson.”…”[2] Falkland Islands Magazine 1889-1916

Reading this article, and looking at the photographs, it is shocking that no crew members died when the rigging came down. Wavertree was not considered worth repairing, and her hull was sold to become a floating warehouse ending her days as an ocean wanderer.

When Wavertree came to the Seaport Museum, after 40 years as a floating warehouse and sand barge, the photographs of her dismasting did not travel with her. For a time no one at the Museum even knew the photographs existed. They turned up during the years-long international search for the ship’s documentation and history by Museum’s friends, advisors, and researchers.

Norman Brouwer, who joined the Museum as Ship Historian in 1972, described how he found the plates during a visit to Port Stanley in an article for Sea History in 1982:

“Still later, on a visit in January…we almost literally stumbled upon the original glass plate negatives from which these photographs had been made! This discovery gave us razor-sharp images to study for our restoration work on the ship. One of the students in the photography class..found glass plates obstructing his parking of his bike in a garage…they were the original plates made when the ship lay dismasted but unbowed, rolling at anchor under leaden skies in Stanley after the frightful beating she’d received off Cape Horn sixty years before.”[3] “The Quest of the Truth of Wavertree” by Norman Brouwer. Sea History, Winter 1982-1983. p. 12.

Mr. Brouwer brought back three prints and one glass plate negative to the Museum, adding them to the archives in the Museum’s maritime reference library. In 2017, our Collections Manager decided to propose these precious items for a postume accession into the permanent collection, in order to better track and take care of them, and I had the rewarding task of assisting in the thorough review of their provenance. Thankfully, the prints had credit lines inscribed on the back reading “c. Joe King/ Stanley Senior School Photography Club/ Peter Gilding.”

Based on the inscriptions and Norman Brouwer’s Sea History article, it was thought that Joe King was the “student” who rediscovered the negatives and brought them to the Stanley Senior School Photography Club to be contact-printed. However, this turned out to not be the full story!

A few years passed, and when we used them for a social media post, we credited them to “Joe King, a student and member of the Stanley Senior School Photography Club.” A few months later, we received a comment on the post from Robert John King, the son of the late Joe King. Mr. King cleared up the identity of the Stanley Senior School student. He wrote:

“A small correction if I may. I remember the subject glass plate and resulting image very well. My father, the late Joe King, acquired a small collection of plate glass negatives of mainly a maritime nature when he took over a small building which had been the photographic studio of a Mr. Dettleff. My father was not a member of the Stanley Senior School Photography Club but was a keen photographer. He had also developed his own films when he was a younger man. When I was in my final year at school I sneaked a few of his glass negatives to my student friends to see what images they could create. Initially they could only create images straight to paper, the same size as the plates. But then a way to make larger images was devised by rigging the enlarger so as to project images onto much larger sizes of paper on the floor. I then showed some of the results obtained to my father who then agreed for the other class [sic] plate images to be used by the club as well. Following this, many other glass plates were obtained from other people who had such lying about. The result was an excellent and comprehensive [sic] portfolio of historical photographs for our national archives. Quite a few folk here have copies of the Wavertree photographs because they are indeed so very impressive!”

It turned out that Robert John King was the student Norman Brouwer mentioned! Thankfully Robert King decided to bring those negatives to be developed by his friends so many years ago, since that is what led to Joe King donating the one negative and the Stanley Senior School prints to the Museum.

With this post I didn’t just want to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Wavertree coming to the South Street Seaport Museum. I also want to thank and send my deepest appreciation to the amazing people that have cared for her, from volunteers to waterfront staff, to members, donors and her recent restoration funders. Lastly, since I am working to preserve, interpret, and share the holdings of the institution I especially appreciate the archivists, collections managers, maritime historians, researchers, and curators that stewarded her history to go along with the living ship that is docked at South Street today.

And let’s not forget how sometimes our social media channels can be critical elements of contemporary research and documentation!

Additional readings on Wavertree, traditional square-rigged ships, and Cape Horn:

“Barons of the Sea: And Their Race to Build the World’s Fastest Clipper Ship” by Steven Ujifusa, 2018

“A Dream of Tall Ships” by Peter & Norma Stanford, 2013

“The Last Time Around Cape Horn: The Historic 1949 Voyage of the Windjammer Pamir” by William F. Stark and Peter Stark, 2003.

“The Peking Battles Cape Horn” by Irving Johnson, 1997.

“The War with Cape Horn” by Alan Villiers and Adrian Small, 1971.

“Wavertree: An Ocean Wanderer” by George Spiers, 1969.